Did you know that Linkedin now has 300 million users, which is about 1 in 3 professionals worldwide? And that 35% of those users log in every day?

And did you know that about 60% of jobs are estimated to be obtained through ‘who you know’ rather than direct application? Did you also know that between 80 and 90% of university graduates only apply for jobs using direct application methods?

70% of learning in the workplace happens informally, much of it problem-based and self-directed, and about 90% of that involves social interaction – either face to face, online or both.

One recent study found that 86% of professionals use online social networks for professional purposes in the workplace. What do they use them for? networking within and outside the organisation, research and learning, and sharing resources and project information with colleagues.

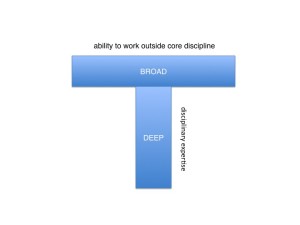

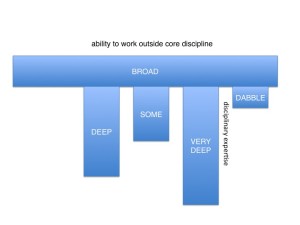

Graduate Employability 2.0 is about all of these things. It explores a different way of engaging with learning and teaching for life and career post-university. Graduate Employability 1.0 was about skills, knowledge, and attributes that individual students can learn in order to be able to obtain or create work and perform well in work situations. In the Graduate Employability 2.0 era, individual skills, knowledge and attributes are still important, but so are the individual’s professional relationships and networks, and what they do with them. The ‘2.0’ signifies the central importance of the social, digitally networked world in which we now all live.

My 2015-2016 Australian Office of Learning and Teaching National Senior Teaching Fellowship seeks to identify the best ways to develop students’ capabilities to build and use professional connections, both online and face-to-face, for career development, creativity and problem-solving, and professional learning, all of which are essential to employability in the digital age.

|

Career development

|

Professional relationships, networks and social capital are vital to career development:

|

Innovation, creativity and problem solving |

Innovation and problem solving thrive on complex collaborative contexts:

|

Professional learning |

Social connections facilitate the reciprocal transmission of skills and knowledge for professional learning:

|

What does the fellowship involve?

Right now I am seeking cases of teaching practice, particularly in humanities, arts and social sciences (HASS) disciplines, that engage with these kinds of learning, and also some examples of graduates who are making the most of their social connections for professional purposes. Chosen cases will be included in a graduate employability toolkit and promoted nationally. If you are interested in being a case study, please get in touch.

I will be surveying all of the universities in Australia to find out to what extent and how they are engaging with teaching for the development of students’ professional connections.

Later on this year I’ll be working with four universities to build graduate employability 2.0 capabilities into their undergraduate programs. We’ll be doing some experiments and seeing which are the best ways to build professional networks into the curriculum

There will be a national symposium hosted at QUT, and I will launch an online community of practice for sharing, discussion and updates very shortly. Watch this space for details!