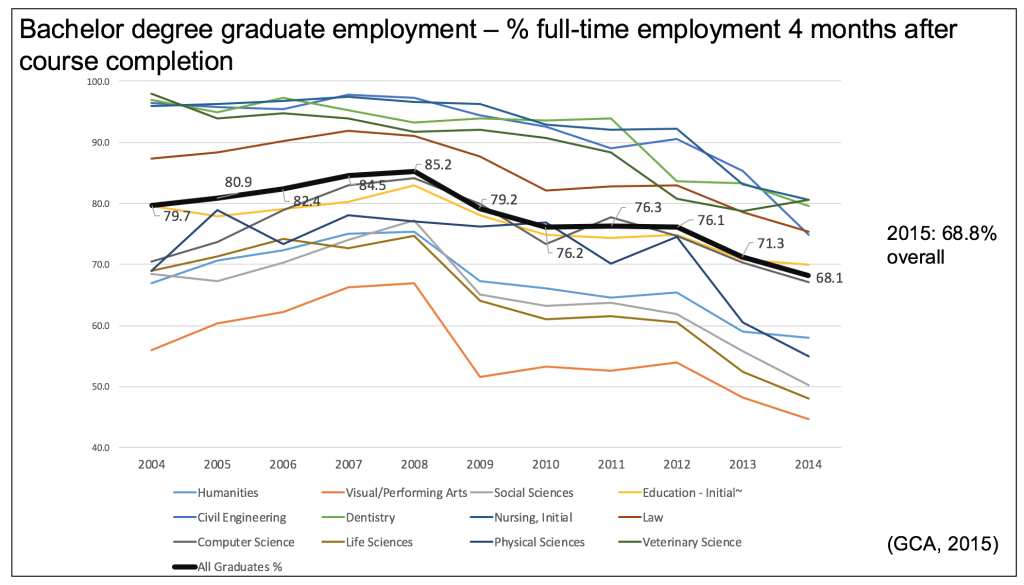

Recently, Australian universities have become highly concerned about graduate employability, and how to ensure that our graduates have positive career outcomes. It’s not that we didn’t care about this before — but recent graduate outcome statistics show that that chances of students gaining full-time employment after graduation are declining in all disciplines, and have been for a few years now. University education represents a signficant investment for students, both in terms of time and effort and course fees, and increasingly want to know that there will be a job for them at the end.

The chief metric that the higher education sector uses to demonstrate positive outcomes is full-time employment 4 months post course completion. This metric comes from graduate surveys known as the Graduate Destintation Surveys (GDS), until recently administered by Graduate Careers Australia.

Under the new QILT (Quality Indicators in Learning and Teaching) system, there are a range of other indicators as well — including a survey of graduate employers asking about graduate employees’ capabilities. There is also a ‘3-year out’ survey of graduate outcomes. The QILT website allows people to compare courses and universities using these indicators. However, the chief metric that is reported and used is still the short-term full-time employment metric, along with median graduate salary.

The short-term full-time employment metric can be useful as an indicator in some respects. For instance, Tom Karmel of the National Institute of Labour Studies, has recently used the GDS to show that more than 50% of the variance in declining graduate outcomes is due to a softening labour market and an oversupply of graduates, particularly in some fields. This has been exacerbated by the introduction of the ‘demand driven system’, and uncapping the number of university places that can be offered in Australia*. The sector is on track to meet its 40% university participation by 2020 target.

Another example of an interesting use of the graduate destination full-time employment metric comes from Denise Jackson from Edith Cowan University, who demonstrated the importance of social capital to initial graduate outcomes, also using statistical modelling of the GDS survey data (in her 2014 study, there was a 54% increase in the chances of full-time job attainment if social network strategies were used).

However, the full-time employment metric we use is problematic in important ways. I summarise these issues as: (i) full-time employment as an employee, (ii) employment is different from employability; and (iii) short-term, narrow outcomes.

1. Full-time employment as an employee. The metric has long been criticised by educators in the arts and creative industries, where the portfolio career (multiple job-holding, self-employment) is ubiquitous – as, of course, is underemployment. But in fields where self-employment and multiple job-holding are common, the ‘full-time employment as an employee’ metric does seem less relevant**. It also might be less relevant across the board in coming years as the traditional organisational career continues to decline, and more and more people are engaged in self-managed, portfolio careers. There is evidence that this is occurring already: while Australia’s overall unemployment rate is steady, the rate of part-time and short-term work overall, and casual jobs for young people 18-24, is increasing. Eighty-six per cent of the new jobs created in Australia last year were part-time. Across OECD nations, 20% of all jobs terminate within one year, and 33% terminate within 3 years. In the US, 40% of work is contingent.

There are also the phenomena of ‘uberisation’ of work, and the start-up economy. While self-employment is actually declining across Australia (according to ABS statistics), more and more people are engaged in informal, self-generated and distributed models of work and income earning through platforms such as Uber, Airtasker (Upwork in the US), and AirBnB. There is also much talk and policy about fostering a start-up economy, particularly in STEM fields, as a way to promote economic growth and social well-being in Australia. It seems that historically, an entrepreneurial career path has not often been chosen by recent graduates, and entrepreneurship is something that tends to be adopted with greater career experience – but it is something that is increasingly being encouraged.

My overall point is this: The national graduate outcomes data collection is the only one we have. If the survey doesn’t include measures of more complex job and career arrangements, we have no way of knowing exactly what’s going on for graduates across Australia. For disciplines where full-time employment is less relevant, and as full-time employment as an employee becomes less common across the economy, it seems less and less useful as a way of describing the outcomes of recent grads.

But of course the GDS (now the GOS in QILT) isn’t just used to describe outcomes — it’s used to benchmark universities and courses against one another. This brings me to my next reservation: employment is very different from employability.

2. Employment is different from employability.

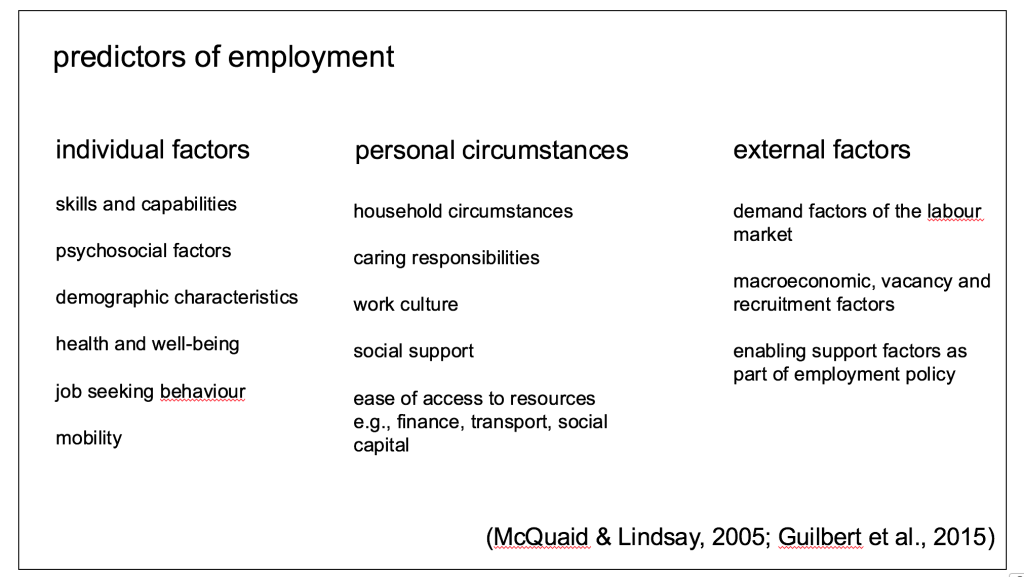

In the last few years, graphs of our declining graduate outcomes like the one above have been used to argue that universities need to be doing more to enhance our students’ employability. However, there are actually a wide range of stronger influences on whether a graduate is employed or not, including (as Tom Karmel points out) the degree of competition for entry-level jobs, and the availability of roles. In 2005, McQuaid and Lindsay published a theoretical framework – one of many – of influences on employability and employment, which they summarise as ‘individual factors’, ‘personal factors’, and ‘external factors’. The traditional remit of universities has been just one element of these: skills and capabilities, and perhaps also some psycho-social factors that can be learned, such as confidence, proactiveness and resilience.

I’d argue that there are indeed things universities can do, and can do better, to enhance their students’ employability (and also, while we’re at it, their citizenship and sustainability capabilities). But using graduate outcomes as the benchmark is leading universities to do things that are outside the traditional capability remit, in seeking to compete for one another for students — such as direct interventions around graduate recruitment, and changing the range and types of courses that they deliver to choose those with better short-term full-time employment outcomes. Universities with regional campuses in areas where there is higher unemployment are at a disadvantage in the benchmarking– and I would hate to see them move out of regions and stop offering degrees to people from diverse backgrounds because the graduate employment outcomes might be lower in these regions.

3. Short term, narrow outcomes.

In a context where our KPI is short-term, full-time employment outcomes, universities are more and more ‘teaching to the test’ — which means we are paying close attention to employer surveys where desired graduate employabiliy skills are listed out (interpersonal skills, written communication etc), and we are paying close attention to the skills that professional accrediting and registering bodies say that they need. The idea is to make graduates as ‘oven ready’ as they can be – both in terms of specific technical and disciplinary skills for their professions, and their transferable / generic skills.

One problem here is that the world of work is in massive flux. In teaching to specific outcomes, the danger is that we start encouraging narrow, inflexible career identities, and overly specific, short-term skills. When students graduate in 3 or 4 years’ time, there may not be the demand for (for instance) print journalists, primary school teachers, or graphic designers, and we need our grads to be able to reinvent themselves and their skills to find and obtain other meaningful work. We don’t teach enough for disciplinary and professional agility.

The CEDA (2015) study into the automation of Australian work suggests that over the next decade, more than 40% of existing job roles will disappear anyway (goodbye taxi drivers and telemarketers!). Other entirely new roles will be created — and while it’s difficult to predict exactly what these roles will be, we’re seeing this already in statistics coming from the US around new jobs in information security, big data analytics, and social media. Further, the roles that will remain are changing, and will require different skill sets. Work roles will require more digital capabilities, emotional intelligence, creativity and complex problem solving, and complex manual dexterity (these kinds of skills are less likely to be automatable).

I also suggest that in this age of uncertainty and unprecedented social change and complexity, where we are confronted by more and more ‘super wicked problems’ — climate change, loss of biodiversity, antibiotic resistance, refugees and asylum seekers, widening gaps between the rich and the poor… and the list goes on — surely we need KPIs around capability development beyond employability skills. I read yet another article this morning about global catastrophic risk (nice reading to go with one’s cornflakes) that predicts our chances of destroying ourselves during the 21st century at about 50%. It’s hard to give exact probabilities on these kinds of things. However, the people who are graduating from our universities will lead our world in the coming decades — they need the capabilities to engage with and manage complex social, cultural, economic, and environmental challenges, as well as to find or create work and perform well in that work.

So, what should we be measuring?

Measurement and benchmarking is an inevitability in this space. It’s difficult to generate suitable, simple benchmarks for our graduate outcomes. I understand why full-time employment is used – it’s simple, and a good indicator of some things. However, we certainly need more nuanced, longer term outcome measures around employment, that embrace self-employment and the portfolio career as well as the metric of ‘short-term full-time work as an employee’.

We need to provide indicators around the actual capabilities that our graduates possess, and their behaviour (such as setting up their own enterprises, if that’s what we want). These indicators need to include capabilities beyond short-term employability skills, to encompass broader employment outcomes and the changing world of work. Finally, I think we need to include social, cultural, and environmental capability indicators, and those of critical thinking and learning, as well as employability skills.

In turn, we need the infrastructural, HR and policy supports in place so that our graduates are able to make the most of their capabilities. We need a labour market that can accommodate our skilled young people, and where they can make meaningful contributions.

——————————-

*the solution doesn’t seem to be to re-cap the number of places offered. In fact, Andrew Norton offers some interesting commentary about how limiting the number of places in courses actually results in worse labour market mismtaches than we have at present. He provides the example of the 1990s Government restrictive caps on medical student places, and points out that this resulted in widespread shortages of doctors, something that was eventualy mitigated by inviting many more overseas-qualified doctors to practice in Australia.

** I should note here that the graduate outcomes survey does include a measure of ‘part-time employment – seeking full-time employment’ — but it isn’t detailed enough to describe employment patterns.