TLDR: My Australian National Senior Teaching Fellowship report is now out and available for download. My fellowship explores the roles that social networks play in graduate employability, and how universities can foster social network capability through interventions at curricular, pedagogic, and organisational levels.

My fellowship findings and resources will be of interest to Australian university leaders who are developing strategies in response to the National Priorities and Industry Linkage Fund, and to educators who are designing or reviewing degree programs.

Readers can access the connectedness reflection tool for educators for free. I also offer facilitated sessions to support educators with curriculum development and review, and strategic industry partnership development. Please get touch if you’d like to find out more.

Full article:

As many of you know, I’m interested in how education can ensure that learners are prepared for the future (and increasingly the now!) of life and work. Some of my research is about the capabilities that individuals can develop – so-called ’21st century’ skills, and the learning & teaching approaches that foster these. But I am also interested in other factors involved in future-capability, beyond individual skills.

For the last five years, through my Australian National Senior Teaching Fellowship Graduate Employability 2.0, along with a range of other research grants, I have been exploring how individuals, educators and educational institutions can enhance and make the most of social networks for learning and career success. I’ve discovered this goes far beyond ‘networking’ and having a polished LinkedIn profile.

How can individuals benefit from social networks?

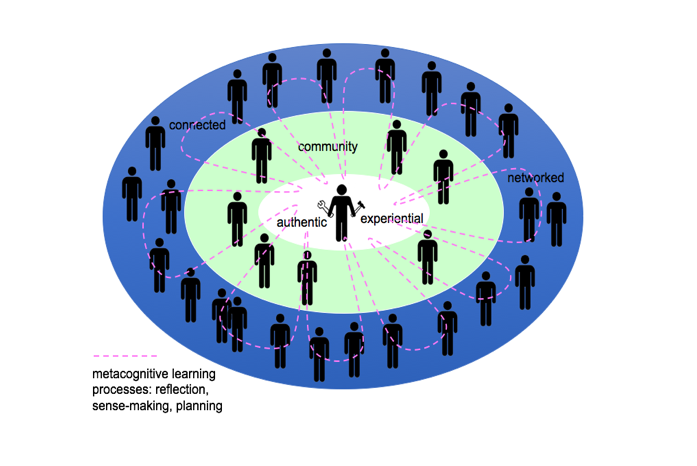

My research suggests that there are at least three ways in which individuals can benefit from social connectedness in 21st century careers. They are:

(1) networks for career development (the one we usually think of) – activating social networks for career development through mentorship, access to resources or opportunities

(2) networks for learning – learning new skills by collaborating with others, or by sourcing information, knowledge or capabilities from others

(3) networks for innovation and problem-solving – solving problems or creating new knowledge by collaborating with, or sourcing information, knowledge or capabilities from, others, particularly those from a different discipline or context

Developing and using networks for learning and innovation / problem solving are centrally important to how 21st century society works.

What does higher education need to do?

Both the capabilities needed for social networks and the social networks themselves can, and should, be developed through higher education. The good news is that over the last few years universities have started to appreciate the roles that networks play in student career development and graduate employability. More and more students are learning the basics of networking for career development while they are undergraduates, which sets a good foundation for social network development over time.

However, learning, problem solving and innovation through social networks are still much less likely to be included in curricula. Since last year much teaching has moved online, but students are still being allocated into teams of 4 with their same-discipline course peers (in a break-out room in Zoom or Teams) to engage in learning. This approach is useful for some outcomes, but it doesn’t get at the real scenarios, processes and outcomes through which graduates will end up adding value.

There are some great exemplars of authentic and ‘free-range’, interdisciplinary and socially networked learning out there — e.g., some kinds of work integrated learning, enterprise and entrepreneurship learning, and research-based learning experiences. I cheer internally every time I hear about one. But this learning is by no means ubiquitous.

The main reasons seem to be that while valuable, it can be more resource-intensive and risky to deliver than classroom-based learning, challenging to arrange logistically and financially, and difficult to assess.

What next steps can educators take?

For social network-based learning to occur effectively and consistently, certain educational elements relating to curriculum, pedagogy and layers of institutional connectedness need to line up. You can access the connectedness reflection tool for educators for free to start to characterise the strengths and opportunities of your program, School, or institution.

More broadly, educational programs and institutions need to be well-connected with their communities and social ecosystems, something which many universities still struggle with. My research interviewees described the university either as a ‘walled garden’ or a series of siloes – neither of which support social network-based learning. My book Higher Education and the Future of Graduate Employability – A Connectedness Learning Approach deals with these issues in more detail, including some case studies from different institutions.

For more information

I encourage readers to check out my fellowship resources:

Final Fellowship Report – Graduate Employability 2.0: Enhancing the Connectedness of Learners, Programs and Higher Education Institutions

The Graduate Employability 2.0 model and framework

Connectedness Reflection Tool for Educators

Fact Sheets

I also offer facilitated sessions to support educators with curriculum development and review, and strategic industry partnership development. Please get touch if you’d like to find out more.